![]()

Early Goldenrod (Solidago Jncea) is one of the many species belonging to the goldenrod genus, Solidago, which includes approximately 100 to 120 known species. These plants are part of the Aster family (Asteraceae) and are widely recognized for their vibrant golden-yellow flower clusters, which typically bloom from July to September. The numerous species of goldenrod often appear very similar, making them difficult to distinguish without close botanical examination.

Despite their bright and showy appearance, goldenrods are frequently, and incorrectly, blamed for causing hay fever in humans. This widespread misconception stems from the fact that goldenrod blooms at the same time as ragweed, a plant that is a major cause of seasonal allergies. However, there is a crucial difference: goldenrod is insect-pollinated, meaning its pollen is heavy and sticky, designed to be transported by bees and other insects. In contrast, ragweed is wind-pollinated, releasing vast quantities of light, airborne pollen that can easily irritate the human respiratory system.

Goldenrod has held cultural significance in various regions. In some traditions, it is viewed as a symbol of good luck or prosperity. While in North America, goldenrods are often regarded as weeds, particularly in pastures and along roadsides, they are appreciated very differently in Europe. British gardeners, for instance, adopted goldenrod as a garden plant long before it gained ornamental popularity in its native range. In formal gardens, goldenrod's tall stems and golden blooms add height, color, and wildlife value to late-summer borders. From an ecological perspective, goldenrods play an important role in supporting biodiversity. The larvae of many species of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) feed on goldenrod. Some of these insect larvae cause the plant to form galls—bulbous tissue masses created in response to larval feeding. These galls provide both food and shelter for the developing insects.

However, the story does not end there. These galls also attract parasitoid wasps, which use their long, needle-like ovipositors to penetrate the gall and lay their eggs inside the larvae. The wasp larvae then feed on the host insect from within. In turn, woodpeckers are known to peck open the galls to extract and eat the insects inside, illustrating a fascinating multi-level interaction between plants, herbivores, parasitoids, and predators. Goldenrod is therefore not just a wildflower; it is a key component of ecosystems, a source of folklore, and a valuable plant for both gardens and wildlife.

![]()

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) has been explored for several commercial and industrial applications, one of the most unusual being its potential use as a natural source of rubber. Certain species of goldenrod produce latex, a milky sap that can be processed into rubber. This idea was famously investigated by inventor Thomas Edison in the early 20th century, who cultivated goldenrod plants over 3 meters tall in an effort to maximize latex production. Edison hoped to develop a domestic source of rubber in response to shortages during wartime.

However, while rubber can be extracted from goldenrod, it has significant limitations. Most notably, goldenrod-derived rubber has poor tensile strength, meaning it lacks the elasticity and durability required for most industrial applications. As a result, despite its novelty and early experimentation, goldenrod rubber has never been adopted on a large commercial scale and remains more of a historical curiosity than a practical resource.

On the other hand, goldenrod continues to enjoy popularity in the herbal and natural health market, especially in the form of goldenrod tea. This tea is made from the dried leaves and flowers of the plant and is commonly found in health food stores and herbal apothecaries. It is traditionally consumed for its diuretic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. Herbalists have long used goldenrod tea to support urinary tract health, alleviate seasonal allergies, and soothe sore throats or inflammation.

![]() Within both rational and holistic systems of medicine, plants in the Solidago genus, commonly known as goldenrods, have long held a place in traditional herbal practices, particularly for their role in supporting kidney and urinary tract health. Herbal practitioners have used goldenrod as a key ingredient in kidney tonics, designed to help reduce inflammation and soothe irritation caused by bacterial infections, urinary tract issues, or kidney stones. The plant’s diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties are believed to help flush out the urinary system, alleviating discomfort while promoting healing.

Within both rational and holistic systems of medicine, plants in the Solidago genus, commonly known as goldenrods, have long held a place in traditional herbal practices, particularly for their role in supporting kidney and urinary tract health. Herbal practitioners have used goldenrod as a key ingredient in kidney tonics, designed to help reduce inflammation and soothe irritation caused by bacterial infections, urinary tract issues, or kidney stones. The plant’s diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties are believed to help flush out the urinary system, alleviating discomfort while promoting healing.

In more intensive herbal detoxification protocols, goldenrod has been used as part of a cleansing tincture to support the kidneys and bladder during a healing fast. These regimens often combine goldenrod with potassium-rich vegetable broths and carefully selected juices, working together to encourage gentle elimination of toxins from the body and support overall urinary function. These traditional uses reflect goldenrod’s broad therapeutic potential, spanning both internal and external applications. While modern clinical studies are limited, goldenrod remains a valued remedy in herbal medicine for its effectiveness in soothing inflammation, cleansing the urinary tract, and providing mild analgesic effects in natural healing systems.

Please note that MIROFOSS does not suggest in any way that plants should be used in place of proper medical and psychological care. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

Early Goldenrod, like many members of the goldenrod family, is considered edible and has a long history of culinary and medicinal use, particularly among Indigenous peoples of North America. Native American tribes utilized various parts of the plant for both nutritional and medicinal purposes. In particular, the seeds of certain goldenrod species were gathered and eaten, either raw or lightly processed. While small, these seeds could be roasted, ground, or mixed with other foraged ingredients to create nourishing meals or to supplement other foods during times of scarcity.

Goldenrod also has a place in traditional herbal preparations. Teas made from goldenrod leaves and flowers have been consumed for their medicinal benefits, including use as a diuretic, a mild anti-inflammatory, and a remedy for respiratory ailments such as colds or sore throats. These herbal infusions are known to have a slightly bitter, astringent taste, often blended with other herbs to enhance flavor and therapeutic effect.

In the realm of apiculture, goldenrod is a valuable late-season nectar source for bees, especially in late summer and early fall when few other plants are in bloom. However, honey derived from goldenrod nectar is often noted for its distinctively dark color and strong, sometimes pungent flavor. This intensity is usually due to admixtures of nectar from multiple late-blooming plants, as bees tend to forage widely. While the taste may not appeal to everyone, goldenrod honey is prized by many for its richness, complexity, and robust mineral content. Though not a staple food, early goldenrod offers diverse uses, from traditional foods and teas to medicinal infusions and flavorful honey, making it a versatile and culturally significant wild plant.

Please note that MIROFOSS can not take any responsibility for any adverse effects from the consumption of plant species which are found in the wild. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

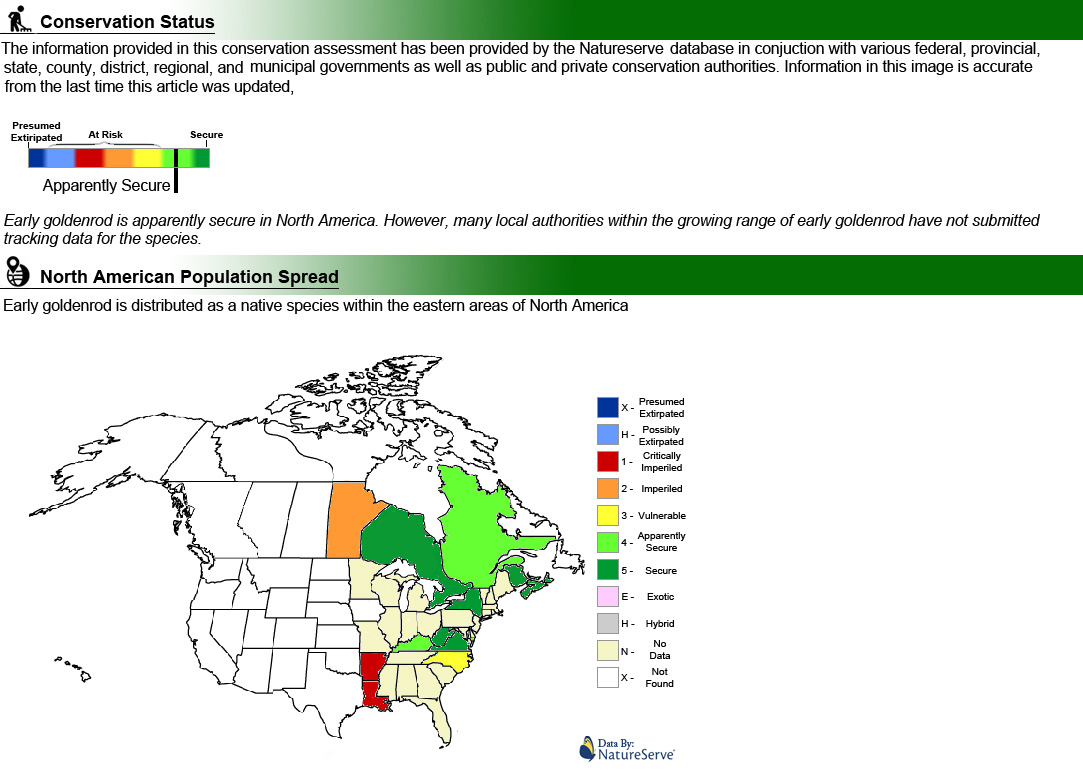

Early Goldenrod is a resilient and widespread plant most commonly found across North America, where it thrives in a variety of natural and semi-natural habitats. It typically grows in meadows, pastures, open woodlands, roadsides, and even abandoned or lightly disturbed cultivated lands. Its adaptability and prolific flowering make it a prominent feature in many late-summer landscapes.

While the majority of goldenrod species are native to North America, a few species are also indigenous to South America and Eurasia, reflecting the plant's broader ecological range and evolutionary success. Despite being a native wildflower in many regions, goldenrod is often labeled a weed by gardeners and landscapers, primarily because of its vigorous growth, tendency to spread, and its mistaken association with seasonal allergies. However, in ecological gardening and pollinator-friendly landscapes, goldenrod is increasingly appreciated for its wildlife value and low-maintenance beauty.

Early Goldenrod, one of the first goldenrod species to bloom in the season, prefers full to partial sun and is best suited to mesic (moderately moist) to slightly dry environments. While it can tolerate moist conditions, it requires well-drained soil to prevent root rot and ensure healthy growth. Early goldenrod is suitable for: light (sandy), medium (loamy) and heavy (clay) soils.

| Soil Conditions | |

| Soil Moisture | |

| Sunlight | |

| Notes: |

![]()

Early Goldenrod is a herbaceous perennial plant known for its upright, elegant form and vibrant yellow blooms. It typically grows unbranched, reaching heights of up to 90 centimeters (approximately 3 feet). The central stem is usually smooth, slightly ridged, and varies in color from green to reddish, depending on environmental conditions.

The plant bears alternate leaves along the stem that are lanceolate in shape, long and narrow with pointed tips. The lower leaves can measure up to 20 centimeters in length and 3 centimeters in width, while the upper leaves become progressively smaller as they ascend the stem. The leaf margins are generally entire (smooth), although they may sometimes be slightly serrated. Occasionally, fine hairs may appear along the edges of the leaves, but the surfaces are typically hairless and smooth.

The inflorescence, the flower-bearing part of the plant, emerges at the apex (top) of the stem and takes the form of a panicle, a branched cluster of flowering stems. These branches often arch upward and outward, creating a shape reminiscent of a fireworks burst or fountain. This graceful arrangement is one of the distinguishing features of early goldenrod.

The plant produces numerous small, bright yellow composite flowers, each measuring 5 to 10 millimeters across. The flowers often emit a mild, pleasant fragrance, which, along with their bright color, attracts a wide range of pollinators, including bees and butterflies. The blooming period typically begins in mid- to late summer and lasts for about one to two months, depending on local climate and growing conditions. Following pollination, the plant produces small fruits called achenes—dry, single-seeded structures. Each achene is equipped with a tuft of fine hairs (known as a pappus) that aids in wind dispersal, allowing the seeds to spread over wide areas.

The root system of early goldenrod is perennial, consisting of a short, woody base known as a caudex, especially in older plants. From this base, the plant may produce rhizomes (horizontal underground stems), which allow it to spread vegetatively, forming small colonies or clumps over time.

![]()

| Plant Height | 60cm to 90cm |  |

| Habitat | Fields, Roadsides, Waste places | |

| Leaves | Lanceolate | |

| Leaf Margin | Entire | |

| Leaf Venation | Longitudinal | |

| Stems | Smooth Stems | |

| Flowering Season | July to September | |

| Flower Type | Elongated clusters of bell shaped florets | |

| Flower Colour | Yellow | |

| Pollination | Bees, Insects | |

| Flower Gender | Flowers are hermaphrodite and the plants are self-fertile | |

| Fruit | Tufted Seeds | |

| USDA Zone | 3A (-37.3°C to -39.9°C) cold weather limit |

![]()

No known health risks have been associated with early goldenrod. However ingestion of naturally occurring plants without proper identification is not recommended.

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see an artist rendering, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of early goldenrod. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see a magnified view, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of the seeds created by early goldenrod for propagation. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

Early Goldenrod can be referenced in certain current and historical texts under the following three names:

![]()

|

What's this? What can I do with it? |

![]()

| Dickinson, T.; Metsger, D.; Bull, J.; & Dickinson, R. (2004) ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto:McClelland and Stewart Ltd. | |

| Blanchan, Neltje (2005). Wild Flowers Worth Knowing. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. |

|

| Kartesz, J.T. 1994. A synonymized checklist of the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. 2nd edition. 2 vols. Timber Press, Portland, OR. | |

| "Goldenrod Rubber". Time Magazine. December 16, 1929. | |

| Campion, K. (1995). Holistic Woman's Herbal - How to Achieve Health and Well-Being at Any Age. Barnes & Noble, Inc. 1995. ISBN 978-0-7607-1030-2 | |

| Kartesz, J.T. 1996. Species distribution data at state and province level for vascular plant taxa of the United States, Canada, and Greenland (accepted records), from unpublished data files at the North Carolina Botanical Garden, December, 1996. | |

| MacKinnon, Kershaw, Arnason, Owen, Karst, Hamersley, Chambers. 2009. Edible & Medicinal Plants Of Canada ISBN 978-1-55105-572-5 |

|

| USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. Wetland flora: Field office illustrated guide to plant species. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| May 31, 2025 | The last time this page was updated |

| ©2025 MIROFOSS™ Foundation | |

|

|