![]()

English Plantain (Plantago lanceolata), also known as ribwort plantain, is a rosette-forming perennial herb that is native to Europe. Over time, it has spread widely across North America, where it is now considered an invasive weed in many regions. Its ability to thrive in disturbed soils, roadsides, pastures, and agricultural lands has contributed to its rapid naturalization. English plantain plays an important role in paleoecology and archaeobotany. It is often used as an indicator of agricultural activity in pollen diagrams, which are tools used by scientists to reconstruct past environments and human land use. Notably, pollen from English plantain has been identified in western Norway dating back to the Early Neolithic period, where its presence is thought to signal the beginning of livestock grazing and land clearing in the area. Chemically, English plantain contains a variety of bioactive compounds.

These compounds are known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In addition, English plantain contains iridoid glycosides, particularly aucubin and catalpol, which are associated with antimicrobial and healing effects and contribute to the plant’s traditional use in herbal medicine. The botanical name of the plant has meaningful roots in Latin. The genus name Plantago comes from planta, meaning “footprint”, likely referring to the shape of the leaf rosette spreading low along the ground. The species name lanceolata means “lance-shaped,” which aptly describes the plant’s narrow, elongated leaves with prominent parallel veins.

![]()

English Plantain has a variety of practical and commercial uses, extending beyond its ecological and medicinal value. One notable application is in commercial bird seed production. The seeds of English plantain are harvested as a nutritious food source for songbirds, making them a common ingredient in bird feed mixes. Their small size and high nutritional content make them particularly attractive to finches and other seed-eating bird species. In addition to its use in animal feed, English plantain also offers potential for fiber production. A strong and durable fiber can be extracted from the leaves, which is said to be suitable for textile applications. Although not commonly used in modern fabric manufacturing, this fiber may have potential for sustainable or traditional textile practices.

Another valuable byproduct of the plant is the mucilage found in its seed coats. When the seeds are macerated in hot water, they release a gel-like mucilage that has historically been used as a natural fabric stiffener. This plant-based alternative to synthetic stiffening agents was once used in household and artisan textile preparation. Additionally, natural dyes can be extracted from the plant. The whole plant is capable of producing gold and brown dyes, which can be used for coloring fabrics, yarns, or crafts. These dyes offer a sustainable, plant-based option for natural dyeing practices and traditional textile arts.

![]() Within both rational and holistic medicine, English Plantain has long been valued for its medicinal properties, and continues to be used in a variety of herbal remedies, particularly in the form of teas, syrups, and topical preparations. One of the most common traditional uses of English plantain is as a cough remedy. A tea made from its leaves is known to be highly effective in soothing the respiratory tract, reducing coughing, and easing throat irritation. The leaves contain a soothing mucilage that coats inflamed tissues, making it especially beneficial for dry or persistent coughs.

Within both rational and holistic medicine, English Plantain has long been valued for its medicinal properties, and continues to be used in a variety of herbal remedies, particularly in the form of teas, syrups, and topical preparations. One of the most common traditional uses of English plantain is as a cough remedy. A tea made from its leaves is known to be highly effective in soothing the respiratory tract, reducing coughing, and easing throat irritation. The leaves contain a soothing mucilage that coats inflamed tissues, making it especially beneficial for dry or persistent coughs.

In traditional Austrian medicine, Plantago lanceolata has been used both internally and externally for a wide range of conditions. Internally, it is prepared as a tea or syrup to treat respiratory disorders, while fresh leaves are applied topically for skin irritations, insect bites, and minor infections. This dual use underscores its versatility as a natural remedy. English plantain is also recognized for its hemostatic properties, it is considered a safe and effective treatment for bleeding wounds. When applied to cuts or abrasions, the crushed leaves can quickly staunch blood flow and help initiate the healing of damaged tissue. This is attributed in part to its content of tannins, which constrict blood vessels, and silicic acid, which supports tissue regeneration. Additionally, extracts from the leaves have been shown to possess antibacterial properties, further supporting their use in treating minor infections and protecting wounds from contamination.

Please note that MIROFOSS does not suggest in any way that plants should be used in place of proper medical and psychological care. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

The young leaves of English Plantain are edible and can be consumed either raw or cooked, though they are not commonly used in modern cuisine due to their bitter flavor and fibrous texture. When preparing the leaves, it is advisable to remove the stringy fibers, which can be tough and unpleasant to chew. This makes the preparation process somewhat labor-intensive. The very young leaves, especially those picked early in the growing season, are more tender and less fibrous, making them better suited for raw consumption in salads or lightly cooked in soups and stews. As the plant matures, the leaves become increasingly coarse and bitter, limiting their palatability.

In addition to the leaves, the seeds of English plantain also have culinary uses. When cooked, the seeds develop a gelatinous texture similar to sago (a starch extracted from tropical palm stems), and can be used as a thickener in puddings, soups, or other dishes. The seeds can also be dried and ground into a fine powder, which can then be mixed with flour to enhance the nutritional content of breads, cakes, or other baked goods. While not a primary staple, the seeds offer a nutritious supplement, rich in dietary fiber and beneficial plant compounds, making them a potential addition to natural or foraged food preparations.

Please note that MIROFOSS can not take any responsibility for any adverse effects from the consumption of plant species which are found in the wild. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

English Plantain is a highly adaptable plant that can thrive in a wide range of soil conditions. It is capable of growing in light (sandy), medium (loamy), and even heavy (clay) soils, provided the soil is well-drained. One of its notable strengths is its ability to survive in nutritionally poor soils, making it common in disturbed or marginal areas such as roadsides, fields, and compacted ground. In terms of soil pH, English plantain is remarkably tolerant. It can grow in acidic, neutral, and alkaline (basic) soils, and is even able to establish itself in very alkaline environments, such as calcareous grasslands and chalky soils. This versatility contributes to its widespread distribution across diverse habitats.

However, English plantain has specific light requirements. It cannot grow in shaded conditions and requires full sunlight to thrive. It does well in both dry and moderately moist soils, making it resilient to fluctuations in water availability. The plant is also tolerant of maritime exposure, meaning it can withstand salty winds and coastal climates, which adds to its success in seaside environments. In addition to its hardiness, English plantain is valued for its ecological role. It is known for attracting birds, particularly seed-eating species, as well as a variety of insects and pollinators that benefit from its nectar and pollen. This makes it a beneficial plant in biodiverse ecosystems and wildlife-friendly gardens.

| Soil Conditions | |

| Soil Moisture | |

| Sunlight | |

| Notes: |

![]()

English Plantain is a rosette-forming perennial herb characterized by its distinctive growth habit and flowering structure. The plant produces leafless, silky, and hairy flower stems that rise to a height of 15 to 50 centimeters above the basal foliage. These upright stems support the reproductive structures and contribute to the plant’s recognizable appearance in fields, meadows, and roadsides.

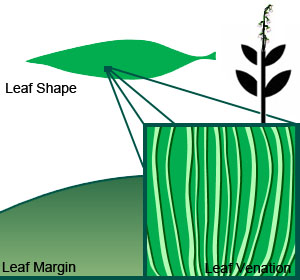

At the base, the plant forms a rosette of lanceolate leaves, which may either spread outward or grow erect. The leaves are narrow with smooth or very lightly toothed edges and feature 3 to 5 prominent parallel veins running the length of each blade. They taper into short petioles (leaf stalks) that are deeply furrowed, forming the base from which the flowering stem emerges.

At the top of each flower stalk is a compact, ovoid inflorescence—a dense, cone-shaped cluster composed of numerous small flowers, each accompanied by a pointed bract (a modified leaf-like structure at the base of the flower). The individual flowers are tiny, measuring only 3 to 4 millimeters in size. Each has four lobes that bend backwards and feature brown midribs, giving the flower head a subtle striped appearance. Prominently extending from each bloom are long, white stamens, which add a delicate, fringed look to the flower spike. The flowers are hermaphroditic, meaning they contain both male (stamens) and female (pistils) reproductive organs. This allows the plant to be self-fertile, capable of producing seeds without cross-pollination from other individuals. However, pollination can also occur through wind, as well as through the activity of flies and beetles, which are attracted to the flower heads.

Each flower has the potential to produce up to two seeds, contributing to the plant’s efficient reproduction and its ability to spread quickly in a variety of habitats. English plantain is well known for its ecological value. It is highly attractive to wildlife, providing food for pollinators, habitat for insects, and seeds for birds. Its presence often indicates a healthy, biodiverse environment and it plays an important role in supporting both wild and cultivated ecosystems.

![]()

| Plant Height | 15cm to 20cm |  |

| Habitat | Fields, Waste places, Lawns | |

| Leaves | Lanceolate 10cm to 40cm long | |

| Leaf Margin | Entire | |

| Leaf Venation | Longitudinal | |

| Stems | Hairy Stems | |

| Flowering Season | May to October | |

| Flower Type | Elongated clusters of spirally arranged flowers on a leafless stock | |

| Flower Colour | White | |

| Pollination | Bees, Insects, Wind | |

| Flower Gender | Flowers are hermaphrodite and the plants are self-fertile | |

| Fruit | Hard ovel seeds | |

| USDA Zone | 5A (-26°C to -28°C) cold weather limit |

![]()

No known health risks have been associated with English plantain. However ingestion of naturally occurring plants without proper identification is not recommended.

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see an artist rendering, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of English plantain. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see a magnified view, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of the seeds created by English plantain for propagation. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

English plantain can be referenced in certain current and historical texts under the following six names:

![]()

|

What's this? What can I do with it? |

![]()

| Dickinson, T.; Metsger, D.; Bull, J.; & Dickinson, R. (2004) ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto:McClelland and Stewart Ltd. | |

| Hjelle, K. L.; Hufthammer, A. K.; Bergsvik, K. A. (2006). "Hesitant hunters: a review of the introduction of agriculture in western Norway". Environmental Archaeology 11 (2): 147–170. | |

| Vogl S, Picker P, Mihaly-Bison J et al. (October 2013). "Ethnopharmacological in vitro studies on Austria's folk medicine--an unexplored lore in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of 71 Austrian traditional herbal drugs". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 149 (3): 750–71. | |

| USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. Wetland flora: Field office illustrated guide to plant species. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| May 31, 2025 | The last time this page was updated |

| ©2025 MIROFOSS™ Foundation | |

|

|