![]()

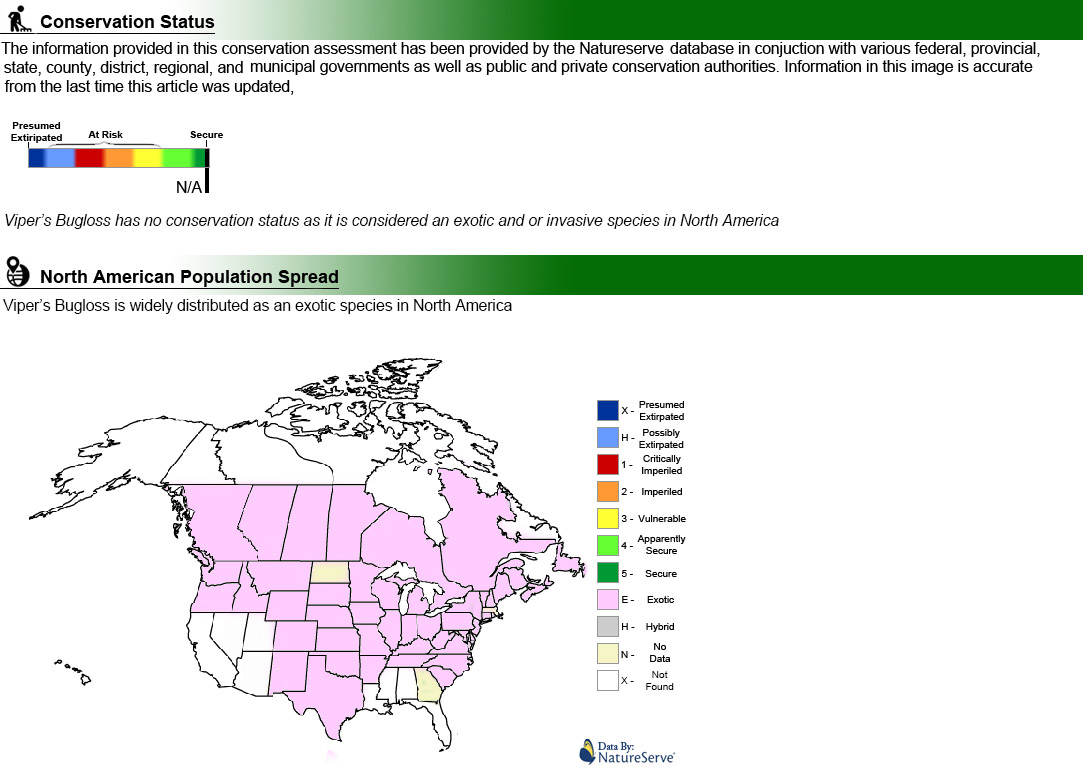

Viper's Bugloss is a striking flowering plant that belongs to the borage family (Boraginaceae). It is native to much of Europe, as well as parts of western and central Asia. Over time, the plant was introduced to North America, where it has since become naturalized. Today, it is particularly widespread in the northeastern regions of the continent. In areas where it is not native, Viper's Bugloss is considered an invasive species. Its rapid spread in non-native environments has led to ecological concerns, prompting efforts to control its growth. Gardeners and conservationists often work to remove it from gardens and natural areas in order to protect local ecosystems.

The scientific name of the plant, Echium vulgare, carries historical significance. The genus name Echium is derived from the Greek word echion, which was the classical Greek name for Viper's Bugloss. The species name vulgare means "common," reflecting its widespread presence. The common name "Viper's Bugloss" has medicinal roots. In the past, the dried plant was used as a traditional remedy for snake bites. This historical association with vipers likely influenced both its common and scientific naming.

![]()

There are currently no commercial applications for viper's bugloss.

![]() Within the traditions of both rational and holistic medicine, Viper's Bugloss was historically believed to offer protection against snake bites, particularly those from vipers, and was also used as a treatment following envenomation. This belief stemmed from the Doctrine of Signatures, a system of thought that held that a plant’s appearance indicated its healing properties. The spotted stems and shape of the plant were thought to resemble a snake, suggesting its use against venom.

Within the traditions of both rational and holistic medicine, Viper's Bugloss was historically believed to offer protection against snake bites, particularly those from vipers, and was also used as a treatment following envenomation. This belief stemmed from the Doctrine of Signatures, a system of thought that held that a plant’s appearance indicated its healing properties. The spotted stems and shape of the plant were thought to resemble a snake, suggesting its use against venom.

Like many other plants in the borage family (Boraginaceae), Viper's Bugloss possesses several physiological effects. Notably, it has diaphoretic (sweat-inducing) and diuretic (urine-promoting) properties, which made it popular in historical herbal medicine for promoting detoxification and reducing fevers. Despite its once-valued status, the use of Viper's Bugloss in modern herbal medicine has significantly declined. This decline is due in part to a general lack of interest in exploring its medicinal potential further, but more importantly because the plant contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids, compounds that are toxic to the liver when isolated or consumed in large amounts over time. Historically, an infusion of the dried plant was taken internally to treat a variety of ailments, including fevers, headaches, and chest congestion. It was also valued for its diuretic action in relieving water retention. Externally, the juice of the plant was used as a soothing emollient, especially beneficial for red, irritated, or delicate skin. Traditional remedies involved applying the plant as a poultice or plaster to treat boils, carbuncles, and whitlows (painful infections around the fingernails).

The leaves were typically harvested during the summer months and could be dried and stored for later use. The roots of the plant contain allantoin, a compound known for promoting wound healing and tissue regeneration. Although no longer widely used in modern herbalism, Viper's Bugloss remains a plant of historical interest, with a long-standing reputation for treating various ailments and for its folkloric role in protecting against snake bites.

Please note that MIROFOSS does not suggest in any way that plants should be used in place of proper medical and psychological care. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

Viper's Bugloss has been listed as a toxic plant. However there are reports that the young leaves can be eaten, raw or cooked and can be used as a spinach substitute.

Please note that MIROFOSS can not take any responsibility for any adverse effects from the consumption of plant species which are found in the wild. This information is provided here as a reference only.

![]()

Viper's Bugloss thrives in calcareous (chalky or limestone-based) and light, dry soils, making it particularly well-suited to coastal environments. It is commonly found growing on sea cliffs, where the soil is well-drained and often exposed to the elements. Beyond the coast, it also establishes itself in disturbed or marginal habitats such as old quarries, gravel pits, and even on stone walls, where other plants may struggle to survive.

The plant is highly adaptable in terms of soil type. It grows well in light (sandy), medium (loamy), and even heavy (clay) soils, provided the ground is well-drained. Remarkably, it can thrive in nutrient-poor soils, giving it a competitive edge in barren or neglected landscapes. In terms of soil pH, Viper's Bugloss is versatile, capable of growing in acidic, neutral, or alkaline (basic) conditions. Viper’s Bugloss does not tolerate shade, preferring full sun to support its growth and flowering. It can handle both dry and moderately moist soil, and is particularly noted for its tolerance to maritime exposure, such as salty winds and coastal spray.

Botanically, the plant produces hermaphroditic flowers, meaning each flower contains both male (stamens) and female (pistils) reproductive organs. This allows the plant to be self-fertile, meaning it can pollinate itself without requiring pollen from another plant. Aside from its hardy nature and adaptability, Viper's Bugloss is well known for attracting wildlife—especially bees, butterflies, and other pollinators, which are drawn to its vibrant blue to purplish flowers and abundant nectar.

| Soil Conditions | |

| Soil Moisture | |

| Sunlight | |

| Notes: |

![]()

Viper's Bugloss (Echium vulgare) is a biennial plant, though it may also behave as a monocarpic perennial—meaning it lives for more than one year but flowers only once before dying. In its second year of growth, the plant typically reaches a height of 30 to 80 centimeters. It is characterized by its rough, bristly surface due to stiff hairs covering its stems and leaves. The leaves are lanceolate in shape—narrow and tapering to a point—and range in length from 1 to 15 centimeters. These leaves grow alternately along the stem and contribute to the plant’s rugged appearance.

The flowers of Viper's Bugloss are arranged in a distinctive, scorpioid cyme, a one-sided, coiled cluster that gradually unrolls as new flowers bloom. Each individual flower initially opens with a pink hue, but as it matures, it transforms into a striking blue, sometimes with purplish tones. The flowers are funnel-shaped, measuring approximately 15 to 20 millimeters in length. These vividly colored and nectar-rich blooms are highly attractive to pollinators. Bees, particularly honeybees and bumblebees, as well as flies and various species of lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), are the primary pollinators of Viper's Bugloss. After pollination, each flower produces a fruit composed of four small, angular nutlets, which serve as the plant’s seeds. These nutlets are typically dispersed close to the parent plant, enabling it to quickly colonize suitable environments.

![]()

| Plant Height | 30cm to 80cm |  |

| Habitat | Fields, Roadsides, Waste places | |

| Leaves | Lanceolate | |

| Leaf Margin | Ciliate | |

| Leaf Venation | Cross-venulate | |

| Stems | Hairy Stems | |

| Flowering Season | June to October | |

| Flower Type | Elongated clusters of funnel shaped florets | |

| Flower Colour | Blue | |

| Pollination | Bees, Insects | |

| Flower Gender | Flowers are hermaphrodite and the plants are self-fertile | |

| Fruit | Small Nutlets | |

| USDA Zone | 3A (-37.3°C to -39.9°C) cold weather limit |

![]()

The following health hazards should be noted when handling or choosing a location to viper's bugloss:

|

TOXICITY Viper's Bugloss contains a number of pyrrolizidine alkaloids. As a member of the genus Borage, it is considered to be potentially toxic. |

|

SKIN IRRITANT |

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see an artist rendering, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of viper's bugloss. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

|

-Click here- or on the thumbnail image to see a magnified view, from The United States Department of Agriculture, of the seeds created by viper's bugloss for propagation. (This image will open in a new browser tab) |

![]()

Viper's Bugloss can be referenced in certain current and historical texts under one other name:

![]()

|

What's this? What can I do with it? |

![]()

| Dickinson, T.; Metsger, D.; Bull, J.; & Dickinson, R. (2004) ROM Field Guide to Wildflowers of Ontario, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto:McClelland and Stewart Ltd. | |

| Fitter, R. & A. (1974). The Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe. Collins. |

|

| Kartesz, J.T. 1994. A synonymized checklist of the vascular flora of the United States, Canada, and Greenland. 2nd edition. 2 vols. Timber Press, Portland, OR. | |

| Kartesz, J.T. 1996. Species distribution data at state and province level for vascular plant taxa of the United States, Canada, and Greenland (accepted records), from unpublished data files at the North Carolina Botanical Garden, December, 1996. | |

| MacKinnon, Kershaw, Arnason, Owen, Karst, Hamersley, Chambers. 2009. Edible & Medicinal Plants Of Canada ISBN 978-1-55105-572-5 |

|

| USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA NRCS. Wetland flora: Field office illustrated guide to plant species. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| National Audubon Society. Field Guide To Wildflowers (Eastern Region): Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40232-2 | |

| May 31, 2025 | The last time this page was updated |

| ©2025 MIROFOSS™ Foundation | |

|

|